2017 has already been quite the busy year in cyber security. This year, the infosec community has already seen one of the biggest ransomware campaigns ever, WannaCry, wreak havoc around the world. However, WannaCry was not the only big story in the cyber security world in the last few months.

WannaCry

We may be only halfway through the year but there can be no doubt that the WannaCry ransomware outbreak will be one of the biggest cyber security stories of 2017.

The WannaCry outbreak began on Friday, May 12, and the ransomware affected hundreds of thousands computers worldwide in a matter of hours.

The ransomware was particularly virulent because of its ability to spread across an organization’s network by exploiting a critical vulnerability in Windows computers called EternalBlue. The vulnerability had been leaked by the Shadow Brokers attack group in April, which said it had stolen the data from the Equation group. The vulnerability had been patched by Microsoft in March, but the attackers took advantage of the fact that many systems remained unpatched.

The WannaCry attackers sought a ransom of $300, however, researchers discovered a flaw in the code that meant the attackers could not track who had paid the ransom, meaning the chances of those who paid the ransom getting their files back were slim. At time of writing, the total amount in the three Bitcoin wallets being used by the WannaCry attackers was approximately $130,000, a relatively small amount given the amount of disruption caused by the ransomware.

Subsequent investigations of the ransomware led researchers to link WannaCry to the Lazarus attack group, which was previously behind attacks on the Bangladesh Central Bank and Sony Pictures.

Longhorn

In March 2017, WikiLeaks published details of what it called the “Vault 7” tools and, in April, Symantec Security Response published a blog about a group called Longhorn, which it had identified using tools and operational protocols outlined in the Vault 7 leaks.

Longhorn was using these tools and protocols to carry out cyber attacks against at least 40 targets in 16 different countries, and researchers determined that there was little doubt that Longhorn’s activities and the Vault 7 documents were the work of the same group.

All of the organizations targeted by Longhorn would be of interest to a nation state actor and its primary targets were in the Middle East, Europe, Asia and Africa. Investigators have evidence that it has been active since at least 2011, with the possibility that is has been active since as far back as 2007.

It is a well-resourced group targeting a global range of targets with well-designed malware and zero-day exploits. Its motivation is intelligence gathering. More information on this group can be found in the Security Response blog on this subject.

Necurs’ return

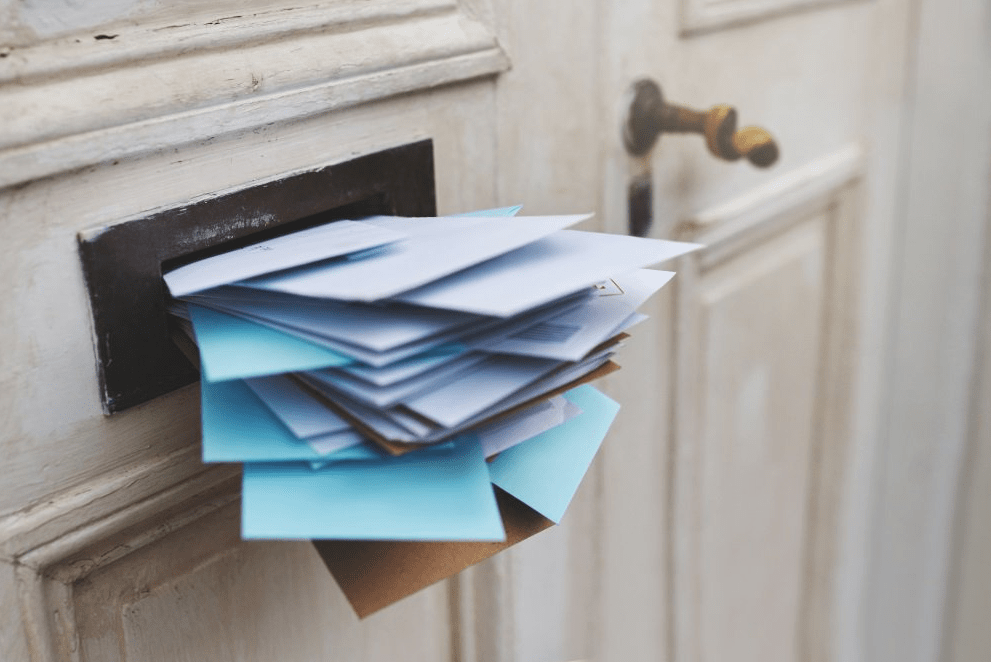

The Necurs botnet dominated email malware campaigns in 2016, leading to a jump in those types of campaigns. However, shortly before Christmas 2016 Necurs ceased activity. While researchers initially thought those behind Necurs were simply taking a break for Christmas, the botnet ceased activity for almost three months, with a resultant sharp drop in the email malware rate.

In December 2016, one in 98 emails blocked by Symantec contained malware. In January this figure was one in 772, while in February it was one in 635 emails blocked.

Necurs resumed its activity on March 20, with Symantec blocking almost 2 million malicious emails sent by Necurs on that day alone. In 2016, Necurs was primarily sending emails containing malware, usually via JavaScript or Office macro downloaders hidden in attachments. However, shortly before its disappearance it started spamming out “pump and dump” stock scams, and since its reappearance it has continued to focus on these types of scams. While the email malware rate has increased since Necurs’ reappearance (it was one in 422 blocked emails in May), it has not returned to 2016 levels.

Middle East attacks

Two pieces of research were published early this year concerning groups, which may be working in coordination, carrying out attacks in the Middle East.

Shamoon, which was originally spotted in 2012 before reappearing in November 2016, continued to be active in attacks in the Middle East in early 2017, with investigations finding tentative links between it and another attack group called Greenbug.

Researchers found that Greenbug was active between June and November 2016 and was targeting organizations in the Middle East with information-stealing hacking tools, including a custom infostealer called Trojan.Ismdoor. Greenbug was present on the systems of an organization that was also compromised by Shamoon in November 2016.

Researchers also discovered that the group behind a third wave of Shamoon attacks in Saudi Arabia, in January 2017, which it calls Timberworm, was also responsible for a wider range of attacks in the Middle East. However, the destructive Shamoon malware (W32.Disttrack.B) was only used against selected targets in Saudi Arabia.

Timberworm compromised organizations using spear-phishing emails and used Office macros or Powershell to gain remote access to the affected computers. The group appears to have gained access to the compromised organizations’ networks weeks, and sometimes months, before deploying Shamoon.

While Timberworm and Greenbug leveraged two distinct toolsets, their targets, tactics, and procedures align very well and in close proximity to the coordinated Shamoon wiping events, meaning it is possible the groups behind these threats are coordinating, possibly at the direction of a single entity.

Watering hole attacks target banks worldwide

In February, attempted watering hole attacks being carried out against banks all over the world became public.

More than 100 organizations in 31 countries were targeted in these attacks, which were discovered when a bank in Poland discovered previously unknown malware running on a number of its computers. The attacks had been underway since at least October 2016. When the Polish bank shared indicators of compromise with other organizations a number of them confirmed they too had been compromised by the previously unknown malware, Downloader.Ratabanka.

The source of the attacks was the website of the Polish financial regulator, which was compromised to redirect visitors to a custom exploit kit that was preconfigured to only infect visitors from approximately 150 different IP addresses, the majority of which were associated with banks.

Investigations into this campaign by researchers established a reasonable possibility that the attackers behind these attacks were associated with the above mentioned Lazarus attack group.

Kelihos/Waledac botnet hit with major takedown

The activities of the Kelihos botnet (also known as Waledec) were halted in April when a Russian man named Peter Levashov, whom the FBI alleges is the mastermind behind Kelihos, was arrested in Spain.

Data indicates that Kelihos ceased activity on April 7. Prior to this date it had been involved in two spam campaigns, as well as a long-running phishing campaign aimed at stealing banking credentials.

Kelihos is a resilient threat that had been active since 2008. It was previously hit by takedowns in 2010, 2011 and 2012, however, it managed to rebuild its operations. Only time will tell if this takedown is a fatal blow to the botnet.

Bachosens

A recent investigation by researchers into the actor behind an advanced malware discovered on the systems of a number of large organizations did not end how researchers had expected. The malware, Trojan.Bachosens, was so advanced that investigators originally thought it was the work of nation state actors. However, further investigations revealed it was the product of what was essentially a 2017 version of the hobbyist hackers of the 1990s. However, this hacker wasn’t out for bragging rights, he was out for financial reward.

A complex investigation by researchers discovered that the individual behind Bachosens was a lone wolf cyber attacker based in Eastern Europe. His primary aim appears to have been to steal autotech software from a company in China, which he then sold on underground forums for relatively modest profit. Researchers were able to discover a lot about this hacker’s activities because, while the malware he used was advanced, he also made some basic mistakes.

Originally shared on Medium.